What to Do If Your Loan Payment Bounces

A bounced loan payment is more common than many borrowers realize, and in most cases, it's fixable. When a payment is marked as "bounced," "returned," or "NSF" (non-sufficient funds), it means the bank couldn't complete the transfer from the borrower's account to the lender. While this situation can feel stressful, understanding what happens next and taking prompt action can help minimize fees, protect credit scores, and prevent more serious consequences.

Key Takeaways

- Bounced payments don't automatically damage credit scores, but late payments reported after 30 days past due remain on credit reports for seven years.

- Banks charge NSF fees ($25-$35) and lenders charge returned payment or late fees ($15-$30), though first-time occurrences may qualify for waivers.

- Proactive communication often results in fee waivers, payment extensions, or hardship accommodations that aren't available to borrowers who wait.

- Most payment failures stem from timing mismatches, which can be eliminated by requesting due date changes to match income schedules.

What It Means When a Loan Payment Bounces

A bounced loan payment occurs when a bank or financial institution cannot successfully process a payment withdrawal. Several common scenarios can trigger this:

- Insufficient funds remain the most frequent cause. When the account balance falls below the payment amount at the time of processing, the bank declines the transaction. This can happen even when funds were available earlier in the day, as banks process transactions in specific sequences that may deplete the account before the loan payment attempts to clear.

- Timing mismatches between paycheck deposits and automatic payment dates create problems for many borrowers. ACH (Automated Clearing House) payments typically take 1-3 business days to process, but deposit timing varies by employer and bank. A payment initiated on Friday may attempt to clear before Monday's paycheck deposit posts, even though both occur within the same pay period window.

- Bank holds and overdraft limits can prevent payments from processing even when total deposits exceed the payment amount. New deposits may be subject to holds, and accounts with opted-out overdraft protection will decline transactions rather than allowing negative balances.

- Account closures, frozen accounts, or expired debit cards will cause payments to fail. Borrowers who recently changed banks or received replacement cards due to fraud may forget to update automatic payment information with lenders.

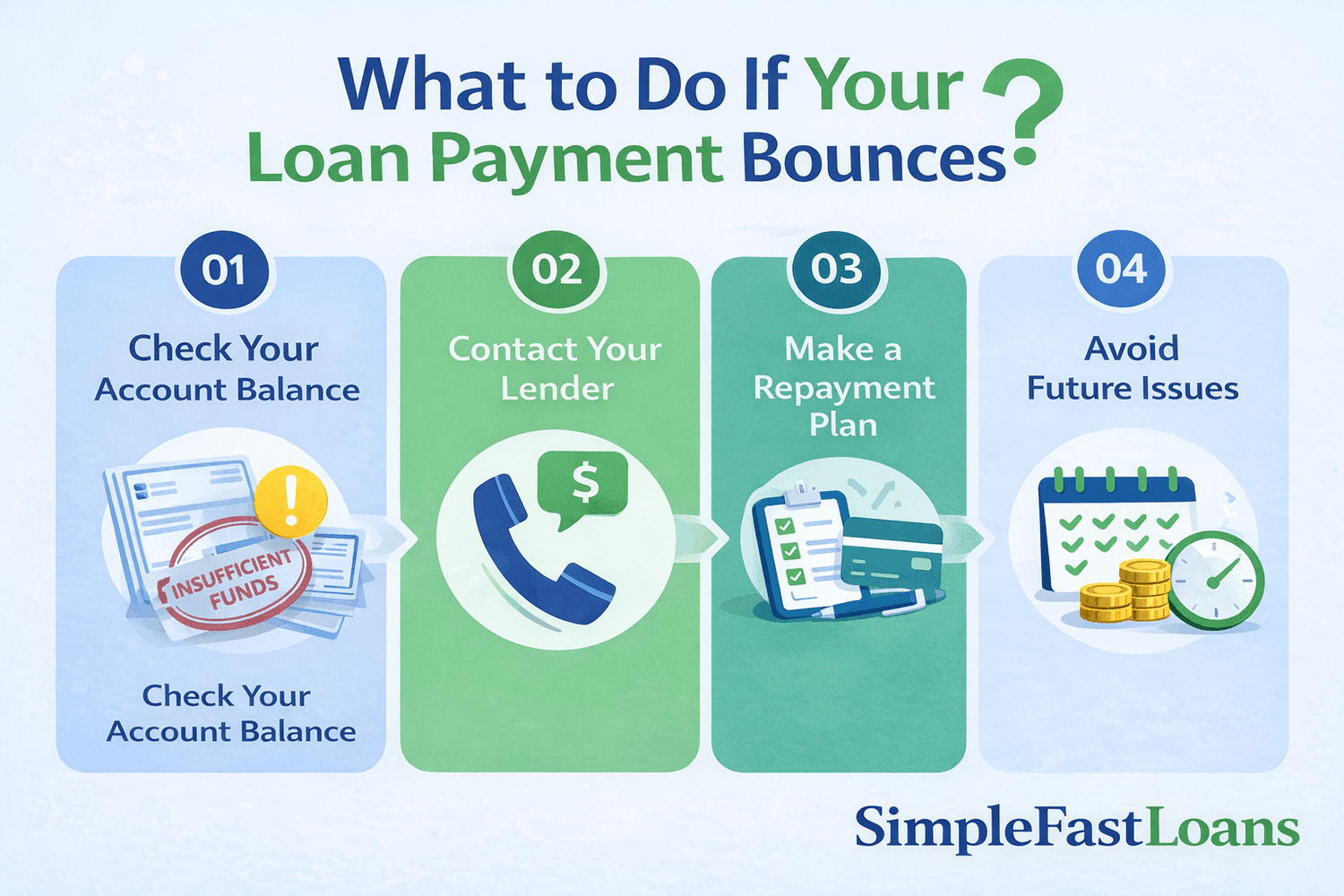

What to Do Immediately If Your Loan Payment Bounces

Taking prompt, strategic action after discovering a bounced payment minimizes financial damage from overdraft fees and demonstrates good faith to lenders. The following steps, executed in order, provide the most effective response.

Step 1: Check Your Account Balance and Bank Activity

Before contacting the lender, verify the exact situation by reviewing bank account activity. Log in to online banking or contact the bank directly to:

- Confirm the specific reason the payment bounced—insufficient funds, holds, technical errors, or account restrictions each require different solutions

- Review pending transactions and holds that may not appear in the available balance but could affect future payment attempts

- Check for overdraft protection status to understand whether the bank will cover future payment attempts or decline them

- Identify the timing of when funds will be available, particularly if awaiting a paycheck deposit or transfer

This information provides concrete details for the conversation with the lender and helps determine realistic timeframes for making the payment. Documentation of the account status such as screenshots or transaction histories can also support requests for fee waivers if the bounce resulted from a bank error rather than truly insufficient funds.

Step 2: Contact Your Lender (Before They Contact You)

Proactive communication significantly improves outcomes. Lenders view borrowers who reach out immediately more favorably than those who avoid contact, and early communication often results in reduced penalties or additional accommodation options.

When contacting the lender, borrowers should be prepared to:

- Explain the situation briefly and honestly without excessive detail or excuses

- Request specific accommodations, such as fee waivers (particularly for first-time occurrences), extended grace periods before late fees apply, or agreements not to retry the payment until a specific date when funds will be available

- Ask about the payment reattempt schedule to avoid multiple failed attempts and associated fees

- Confirm the total amount now due, including any fees already assessed

- Document the conversation by noting the representative's name, date, time, and any agreements reached

Many lenders have formal hardship programs or first-time forgiveness policies that customer service representatives can apply, but these accommodations usually require the borrower to initiate the request. Waiting for the lender to make first contact eliminates access to some of these options.

Step 3: Make the Payment as Soon as Possible

If funds are available or will be available within a day or two, submitting payment immediately prevents compounding problems. However, payment method and timing considerations matter:

- Same-day payment options include debit card payments (which process immediately), wire transfers (expensive but instant), or in-person payments at physical lender locations. These methods typically carry higher fees than ACH transfers but provide immediate confirmation and stop late fees from accumulating.

- Next-day or standard ACH payments cost less but take longer to process. If the payment will still arrive within any applicable grace period, this delay may be acceptable. However, borrowers should confirm with the lender whether additional late fees will accrue daily or if making the payment within a specific timeframe will limit total fees.

- Avoid allowing automatic reattempts if funds remain unavailable. Contact the lender to cancel scheduled retries and arrange a specific date for manual payment submission once funds are truly available. This prevents multiple NSF fees and additional returned payment charges.

If You Can't Make the Payment Right Away

When immediate payment isn't possible, borrowers have several options that can prevent more serious consequences. These alternatives work best when arranged proactively rather than after further delays.

Short-Term Options to Ask Your Lender About

- Payment extensions allow borrowers to push the due date back, typically by 5-15 days, without the payment being considered late. Not all lenders offer extensions, and availability often depends on the loan type and the borrower's payment history. Extensions may carry nominal fees (usually $10-$25) but help avoid larger late fees and credit reporting.

- Due date adjustments permanently change future payment due dates to align better with income schedules. Borrowers whose paychecks arrive mid-month but have payments due at the beginning of the month can request a permanent due date change. This modification usually affects all future payments rather than just the current late payment, preventing recurring timing issues.

- Temporary hardship accommodations include various programs depending on the lender and loan type. Options may include reduced payment amounts for a limited period, interest-only payments temporarily, skipping one payment and adding it to the end of the loan, or formal forbearance periods. These programs typically require documentation of financial hardship (job loss, medical expenses, etc.) and may affect loan terms or total interest paid.

If the Payment Is Part of an Installment Loan

Installment loans—personal loans, auto loans, and mortgages with fixed monthly payments over a set term—have specific policies for handling missed payments that differ from revolving credit like credit cards.

Most installment lenders distinguish between delinquency and default.

- Delinquency begins immediately when a payment is late, but doesn't necessarily trigger severe consequences right away. The loan remains active, and bringing the account current through payment resolves the delinquency status.

- Default occurs when delinquency persists for an extended period (commonly 90-120 days) or when specific loan agreement terms are violated. Default can trigger loan acceleration clauses that make the entire remaining balance due immediately.

For a single bounced payment on an installment loan, the immediate priority is bringing the account current before it reaches 30 days past due. Most installment lenders will work with borrowers on first-time late payments, particularly if the overall payment history has been strong. However, patterns of bounced payments or chronic lateness significantly reduce lender willingness to offer accommodations.

Borrowers struggling with installment loan payments should explore restructuring options before the situation worsens. Some lenders offer loan modifications that extend the repayment term to reduce monthly payments, though this increases total interest paid. Understanding how installment loans work, including the difference between principal, interest, and how payments are applied, helps borrowers make informed decisions about restructuring or alternative solutions.

Understanding Different Types of Payment Failures

Financial institutions and lenders distinguish between different payment failure types, which can affect fees and processing:

- Returned ACH payments occur when a bank processes but then reverses an electronic transfer. The payment may initially show as pending before being returned, typically with an NSF or "insufficient funds" code. Lenders may automatically reattempt ACH payments after a few days, potentially triggering additional fees with each attempt.

- Declined debit card payments are rejected immediately at the point of authorization. The transaction never enters processing, so the borrower's account may show no record of the attempt. While this prevents some bank fees, lenders still typically assess late payment charges.

The distinction matters because ACH returns often incur both bank NSF fees and lender returned payment fees, while declined cards may only trigger lender late fees. Additionally, some lenders retry failed ACH payments automatically but require manual resubmission for declined card transactions.

Fees You May Be Charged After a Bounced Loan Payment

Bounced loan payments typically trigger multiple fees from different institutions, and understanding each charge helps borrowers anticipate total costs and identify potentially improper fees.

| Category | Fee Type | Charged By | Typical Cost | How/When Applied | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALLOWED FEES | NSF (Non-Sufficient Funds) | Your bank | $25–$35 per occurrence | When the bank declines a transaction due to insufficient funds | • Some banks charge per transaction; others cap daily NSF fees • Charged regardless of the reason for failure • Applied to your bank account |

| ALLOWED FEES | Returned Payment Fee | Your lender | $15–$30 | When payment fails to clear, regardless of the reason | • Varies by lender and loan type • Separate from (in addition to) bank NSF fee • Applied even if the bank error caused failure |

| ALLOWED FEES | Late Fee (Fixed) | Your lender | $15–$25 flat amount | After the grace period expires (typically 5–15 days past due date) | • Structure depends on loan terms and state regulations • Applied once per missed payment • Timing varies by lender policy |

| ALLOWED FEES | Late Fee (Percentage) | Your lender | 5% of payment amount | After the grace period expires (typically 5–15 days past due date) | • Common for larger loans • Can be more expensive for high payment amounts • State regulations may cap the percentage |

| ALLOWED FEES | Reattempt Fee | Bank and/or lender | Same as NSF + returned payment fees | Each time lender automatically retries a failed ACH payment | • Can result in multiple fee sets ($40–$65 each) • Not all lenders retry automatically • Usually limited to 1–2 retry attempts |

| PROHIBITED FEES | Undisclosed Fees | N/A | N/A | Cannot be charged | Fees must be clearly stated in the original loan agreement (consumer protection regulations) |

| PROHIBITED FEES | Multiple Late Fees for Same Payment | N/A | N/A | Cannot be charged | Only one late fee per missed payment (though a separate returned payment fee is allowed, as it servesa different purpose) |

| PROHIBITED FEES | Excessive/Punitive Fees | N/A | N/A | Cannot be charged | Fees unreasonably high relative to administrative costs violate state usury laws and unfair lending regulations |

Common Fees to Expect

- NSF and returned payment fees come from two sources. Banks charge account holders NSF fees when they decline transactions due to insufficient funds, typically ranging from $25 to $35 per occurrence. Some banks charge this fee for every declined transaction on the same day, while others cap daily NSF charges. Separately, lenders assess returned payment fees when payments fail to clear, regardless of the reason. These fees typically range from $15 to $30 but vary significantly by lender and loan type.

- Late fees apply when payments aren't received by the due date. Lenders structure these fees in two ways: fixed amounts (such as $15 or $25 per late payment) or percentage-based calculations (commonly 5% of the payment amount). The specific structure depends on loan terms, state regulations, and lender policies. Late fees typically trigger after a grace period expires, which may be 5 to 15 days after the original due date, though this varies considerably.

- Reattempt fees may apply when lenders automatically retry failed ACH payments. If a lender attempts to collect the same payment multiple times and each attempt bounces, borrowers could face repeated returned payment fees from both the bank and the lender. Not all lenders retry payments automatically, and those that do may limit attempts to one or two retries to avoid excessive fee accumulation.

What Fees Are Not Allowed

Consumer protection regulations and state laws prohibit certain fee practices. Lenders cannot assess fees that weren't clearly disclosed in the original loan agreement. Charging multiple late fees for the same missed payment (rather than separate returned payment and late fees, which serve different purposes) typically violates lending regulations.

Excessive fees—those unreasonably high relative to the actual administrative costs of processing a return—may violate state usury laws or unfair lending practice regulations. What constitutes "excessive" varies by jurisdiction, but regulators scrutinize fees that appear punitive rather than compensatory.

How Much Fees Usually Cost

Total costs for a single bounced payment typically range from $40 to $65 when combining bank NSF fees ($25-$35) and lender returned payment or late fees ($15-$30). However, actual amounts vary significantly based on:

- State regulations that cap certain fee types

- Loan type, with personal loans, auto loans, and mortgages having different typical fee structures

- Lender policies, as some institutions waive first-time fees or offer lower charges for borrowers with strong payment histories

- Bank account type, as some checking accounts include overdraft protection or NSF fee forgiveness programs

Borrowers should review both their loan agreement and bank account terms to understand exact fee structures. State-specific lending regulations may impose caps that override standard lender policies, particularly for certain loan products like payday loans or small-dollar installment loans.

Timeline: What Happens After a Loan Payment Bounces

The timeline following a bounced payment significantly impacts fees, credit reporting, and available resolution options. Understanding this sequence helps borrowers take action during critical windows.

|

Timeframe |

What Happens |

What Borrowers Experience |

Actions & Consequences |

|

Day 0–1: Payment Is Returned |

• Banks return ACH payments within one business day |

• Often unaware payment has bounced |

• Lender notes the failure and may assess fees |

|

Days 1–5: Lender Response Window |

• Many lenders automatically reattempt ACH payments 3-5 days later |

• Receive automated emails, texts, or phone calls |

• Late fees trigger (timing depends on grace period) |

|

After 30 Days: Credit & Account Impact |

• Lenders report to credit bureaus monthly |

• Internal "past due" status triggers collections efforts |

• Late payment reported to Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion |

Will a Bounced Loan Payment Hurt Your Credit?

The relationship between bounced payments and credit damage isn't automatic, but timing and lender reporting practices determine the ultimate impact.

- A bounced payment itself doesn't appear on credit reports. Credit bureaus don't receive direct notification when a payment fails to clear a bank account. What appears on credit reports is the late payment that results if the bounced payment isn't resolved quickly enough.

- Late payments and credit bureau reporting follow specific timelines. Lenders typically report account status to Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion once a month. The reporting includes whether payments are current, 30 days late, 60 days late, 90 days late, or in more serious delinquency. The key threshold is 30 days past the due date—most lenders don't report payments as late until they've been unpaid for a full 30 days beyond the original due date.

This creates a crucial window. If a payment bounces on the due date but is made within the following 30 days, many lenders will not report it as late to credit bureaus, even though they may have assessed late fees internally. However, this practice varies by lender, and some institutions have stricter reporting policies.

What Stays on Your Credit Report and for How Long

If a late payment is reported to credit bureaus, it remains on credit reports for seven years from the original delinquency date. However, the impact on credit scores diminishes significantly over time. Recent late payments affect scores much more than older ones, and a single late payment typically has less impact than multiple late payments or a pattern of delinquency.

The severity of credit score impact depends on several factors:

- How late the payment was (30 days late has less impact than 60 or 90 days late)

- How recent the late payment is (last month versus three years ago)

- Overall credit history (one late payment on an otherwise perfect record is less damaging than late payments among other negative marks)

- Credit score starting point (higher scores see larger point drops from late payments, though they typically recover faster)

For borrowers with strong credit histories, a single 30-day late payment might reduce credit scores by 60-110 points initially, though scores often recover within several months if subsequent payments remain current. For those with already lower credit scores, the impact may be 30-50 points.

How to Prevent Future Bounced Loan Payments

Prevention strategies address the root causes of bounced payments and create financial buffers that accommodate timing mismatches and unexpected expenses.

- Align due dates with paydays by requesting due date changes from lenders. Most lenders will accommodate reasonable requests to move due dates, and synchronizing loan payments with income receipt eliminates the most common cause of bounced payments. Borrowers with mid-month paychecks should have mid-month due dates; those paid on the first and fifteenth should schedule major payments shortly after these dates.

- Set balance alerts through online banking to receive notifications when account balances fall below specific thresholds. Setting an alert for when the balance drops below the total of upcoming automatic payments (plus a buffer) provides advance warning to either deposit funds or contact lenders to delay payment.

- Use partial payments if allowed to avoid total payment failure. Some lenders accept partial payments, which can keep loans from entering delinquency even when full payments aren't possible. However, borrowers should verify lender policies, as some institutions apply partial payments to fees and interest rather than principal, and partial payments don't always prevent late fees or credit reporting.

- Maintain a buffer amount in checking accounts equal to at least one month's worth of automatic payments plus $100-$200 for unexpected variations. This buffer absorbs timing discrepancies, unexpected fees, or forgotten transactions that might otherwise cause payment failures. While maintaining a buffer requires financial discipline, it effectively eliminates most bounced payment scenarios.

Bounced loan payments, while stressful, are usually resolvable situations when addressed promptly and honestly. The key to minimizing damage lies in quick action: verifying the cause, contacting the lender immediately, and making payment as soon as funds are available. For borrowers who cannot make immediate payment, proactive communication and requesting available hardship accommodations prevent escalation into more serious delinquency.

Related Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Here are common questions people often ask about bounced payments:

Can a lender retry a bounced payment without permission?

Yes, if the original loan agreement included authorization for automatic payments, lenders typically have permission to retry failed ACH transactions without additional authorization. However, practices vary by lender, and some only retry once while others may attempt collection multiple times over several weeks. The original payment authorization generally covers retry attempts. Borrowers who want to prevent retries should contact the lender to revoke ACH authorization or arrange a specific payment date.

How many days before a bounced payment becomes late?

Grace periods vary by lender and loan type, but bounced payments often trigger late fees immediately or within 5-15 days of the original due date. The critical timeline for credit reporting is typically 30 days past due—most lenders don't report late payments to credit bureaus until 30 days after the original due date has passed. However, internal late fees may apply much earlier, and lenders begin considering accounts delinquent as soon as payments bounce.

Can NSF fees be waived?

Both bank NSF fees and lender returned payment fees can potentially be waived, especially for first-time occurrences. Banks often waive NSF fees for customers with good account histories who request forgiveness, though policies vary by institution. Lenders may waive returned payment or late fees for borrowers with strong payment histories who contact them proactively. Fee waivers are never guaranteed but are worth requesting, particularly when the bounced payment resulted from unusual circumstances rather than chronic insufficient funds.

What if my bank caused the payment to fail?

If a payment bounced due to a bank error—such as incorrectly applied holds, system malfunctions, or mishandled deposits—borrowers should document the error and request fee reversals from both the bank and lender. Banks typically reverse fees for confirmed errors, and lenders will often waive charges when provided documentation that the failure wasn't due to actual insufficient funds. Borrowers should obtain written confirmation from the bank explaining the error to share with the lender.

Is a bounced payment the same as default?

No, a bounced payment and default are different. A bounced payment is a single failed transaction that creates delinquency but doesn't immediately constitute default. Default occurs when delinquency persists for an extended period (commonly 90-120 days), when specific loan agreement terms are violated, or when lenders invoke acceleration clauses, making the entire balance due. A single bounced payment is usually resolved by making the payment late, while default represents a more serious breakdown in the lending relationship with more severe consequences.